In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Key facts

- Most headaches encountered in pharmacy are primary headaches

- Secondary headaches are much more rare, although pharmacists need to be aware of important differentiating red flags

- Primary headaches can be managed with simple analgesics

- Patients with several episodes of migraine would benefit from prophylactic therapy.

Learning objectives

After reading this feature, you should be able to:

- Understand the difference between primary and secondary headaches

- Describe the symptoms of common types of primary headache

- Advise patients on treatment options

- Recognise red flags.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence of more than 90 per cent, headaches are a symptom for which there are a number of different potential causes.

Patients tend to self-manage their headaches with OTC analgesics, although some may be concerned, particularly if a headache persists for some time, that it is a sign of something more sinister, like a brain tumour. Fortunately, most headaches are not caused by brain tumours.

A brain tumour headache is typically worse in the morning, aggravated by straining, coughing, shouting or bending over, with the intensity and pain reducing upon standing upright. This type of headache fails to respond to analgesics.

According to the International Headache Society, headaches are categorised as primary or secondary, with the latter having a clear and understandable origin, such as a ruptured aneurysm or injury.

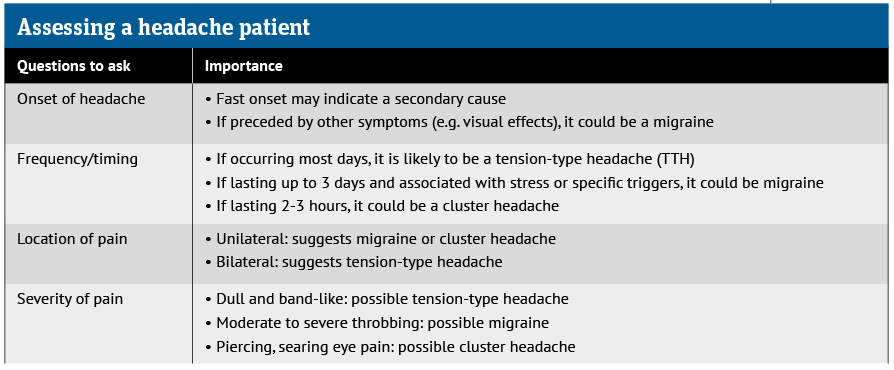

A primary headache is the most common form of headache, accounting for more than 90 per cent of cases. There are three main types of primary headache: tension-type, migraine and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia. This article will focus on the two most common forms: tension-type headache and migraine.

Tension-type headache

This is by far the most common type of primary headache, affecting between 30 and 80 per cent of the population. A tension-type headache (TTH) can be infrequent (occurring less than once a month), frequent (at least 10 episodes taking place on less than 15 days a month) or chronic, in which patients experience more than 15 episodes a month.

Patients with TTH will classically describe the following symptoms:

- A band of mild to moderate pain across the forehead

- A general worsening of pain throughout the day

- A sensation of pressure or tightness, like having a tight band around the head.

The typical history is of a headache with gradual onset that persists for variable periods of time – from half an hour to several days – but with a constant level of pain, sometimes referred to as a dull pain or ache.

While uncomfortable, a TTH does not affect a patient’s ability to sleep and, in most cases, individuals can continue to work.

There are a number of possible underlying causes for a TTH, some of which include:

- Stress, anxiety or lack of sleep

- Eye strain

- Hunger

- Exposure to bright sunlight, heat, cold or noise

- Alcohol, caffeine or even dehydration.

Management

Although a TTH can last for several days, it is not serious and is generally self-limiting. An acute TTH frequently responds well to simple analgesics such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, naproxen or aspirin.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women should use paracetamol. While NSAIDs should be avoided in pregnancy, they can be used during breastfeeding.

Where simple analgesics are ineffective, combination products containing caffeine can be used. Caffeine itself is not effective for acute TTH but it appears to be beneficial in combination with paracetamol, aspirin or ibuprofen.

When combination therapy fails to provide relief, patients should be referred to their GP. This is also the most appropriate action for frequent and chronic TTHs. Typically, low dose tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline up to 100mg/day) or doxepin (up to 100mg/day) are effective.

Migraine

The most debilitating of primary headaches is episodic migraine, which affects around 2 per cent of the general population. Migraine can be further divided into two distinct sub-types:

- Migraine without aura

- Migraine with aura (sometimes referred to as ‘classic’ migraine).

Migraines are described as episodic when they occur for less than 15 days a month, and chronic when there are more than 15 episodes a month for more than three months. A typical sufferer will experience one or two attacks a month.

Migraines are two to three times more common in women and around 8 per cent of sufferers have the chronic type.

While the precise cause of migraine remains unclear, it is probably a combination of genetic, environmental and neurological factors.

Interestingly, between 20 and 60 per cent of migraine sufferers have what is known as an intuitive or prodromal phase, sometimes up to 24-48 hours before the onset of symptoms.

Migraines can be triggered by a number of factors, including stress (most common), disturbed sleep, irregular eating or skipping meals, excessive intake of caffeine, lack of exercise, strong odours and menstruation.

Migraine without aura

A diagnosis of migraine without aura is based on the following criteria:

- A headache lasting 4-72 hours if untreated or unsuccessfully treated

- The presence of at least two of the following characteristics:

- Unilateral (although in 30-40 per cent of cases, the headache is bilateral)

- Pulsating (throbbing)

- Moderate to severe intensity

- Worsened by physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs.

- There should also be at least one of:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Photophobia or phonophobia.

Migraine with aura

Around a third of patients experience an aura with their migraine. A diagnosis of migraine with aura should fulfil the criteria for migraine without aura in terms of duration and characteristics as described above, together with aura symptoms.

Aura symptoms are highly variable in nature, although characteristically they are progressive and occur within an hour before the onset of the headache.

Patients describe seeing zig-zag lines, having blind spots and even changes in vision. Sufferers might also develop sensory symptoms, such as numbness, that are unilateral and felt in one hand or on one side of the face. These symptoms precede the headache itself by up to 60 minutes.

Migraine management

In the first instance, patients should be advised to avoid potential migraine triggers wherever possible.

- Acute attacks

Simple analgesics as a single dose at the start of a migraine will often suffice. For example:

- Ibuprofen 400mg (increased to 600mg if needed)

- Aspirin 900mg

- Paracetamol 1,000mg.

Patients with associated nausea or vomiting can take buccal prochlorperazine 3mg. There is little evidence to support the use of opioids in acute migraine and these should be avoided.

If patients fail to respond to first-line options, then sumatriptan 50-100mg can be taken, either alone or in combination with paracetamol or NSAIDs. For patients who experience an aura, sumatriptan should be taken at the start of the headache and not the aura.

For pregnant and breastfeeding women, paracetamol is the preferred first-line treatment for acute episodes, although sumatriptan can also be used. Aspirin and opiates should be avoided in pregnancy. For pregnant women with nausea or vomiting, short-term use of metoclopramide (not during breastfeeding) and prochlorperazine can be used.

Prochlorperazine can be used short-term in breastfeeding women, although use of buccal prochlorperazine in pregnancy and breastfeeding is not advised.

- Prophylactic therapy

The decision to initiate prophylactic therapy is recommended in cases where:

- Migraine attacks significantly interfere with a patient’s daily activities, despite acute treatment

- Attacks are frequent (on average, more than once a week)

- When acute therapy is either contraindicated or ineffective.

- Where patients are at risk of medication overuse headache.

Pharmacotherapy can include:

- Propranolol 80-160 mg daily (in divided doses)

- Topiramate 50-100mg daily

- Amitriptyline 25-75mg daily

- Candesartan 16mg daily (unlicensed use).

Calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitors in migraine

During a migraine, activation of the trigeminovascular system leads to increased release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which in turn increases the sensitivity of trigeminal nociceptors.

This causes cerebral vasodilation and transmission of pain signals, leading to the intracranial pain seen in migraine.

A new class of drugs, the ‘gepants’, which inhibit the action of CGRP, have been specifically developed for the prophylactic management of migraine.

In clinical trials, gepants caused a significant reduction in migraine pain and relieved associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia and nausea.

NICE has recommended two oral gepants – rimegepant and atoegepant – as preventative therapy for episodic migraine in adults who have at least four but fewer than 15 migraine attacks a month, but only if at least three preventative treatments have proved ineffective.

Medication overuse headache

When treating patients with primary headaches, pharmacists need to be mindful of the risk of medication overuse headache.

This is a headache that is present on at least 15 or more days a month among those with a pre-existing primary headache disorder.

It develops as a consequence of regularly using one or more drugs (in particular, codeine-containing analgesics or even triptans) for symptomatic treatment of acute headaches for longer than three months. It is most commonly seen in patients with migraine but does occur in those with TTH.

Complete withdrawal of all analgesics is recommended, although the headaches are likely to worsen for the first one to two weeks.

Patients may also experience nausea, vomiting, reduced appetite, tachycardia, sleep disturbance, anxiety and restlessness.

Cluster headache

Cluster headaches are the most common type of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia, with a lifetime prevalence of roughly 0.12 per cent.

Most (80 per cent) of people affected have the episodic form and the remainder a chronic form. The headache itself is characterised by attacks (the cluster period) of severe unilateral pain, localised to the orbital, peri-orbital and/or temporal areas.

These attacks can last anywhere from 15 to 180 minutes and occur from once every other day to as often as eight times a day for up to three months, followed by a period of remission.

Acute attacks are managed with subcutaneous sumatriptan, whereas the first-line preventative therapy is verapamil.

Secondary headaches

A secondary headache arises from another condition that is known to cause a headache. Pain severity is not helpful in distinguishing between a primary and secondary headache.

Although uncommon in primary care, important red flags with any headache include:

- Sudden onset and it becomes worse within five minutes (a thunderclap headache)

- Associated neurological problems (e.g. facial muscle weakness or numbness)

- Associated systemic upset (e.g. general malaise, fever or fatigue)

- Headaches in the over-50s – an independent risk factor for an intracranial problem.

Headache & migraine resources

- The BASH National Headache Management System for Adults (2019) is available online at bash.org.uk

- The International Headache Society’s Classification of Headache Disorders can be found at ichd-3.org

- The topiramate pregnancy prevention programme is available at medicines.org.uk/emc/rmm/3083/Document